The common feedback and frustration many business leaders share is the same: they lament that they have hired high-caliber talent for key roles, invested in training to create a high-performing culture and procured the best collaboration tools on the market. However, their teams continue to struggle to deliver a new product.

The unfortunate reality is that while they’ve made some essential investments, environmental and cultural factors are holding the teams back from success. For answers, I turn to this anecdote:

I recently worked with a product organization in which only one team within the group was finding success, while others continued to stall. The group executive would call in the product leadership team monthly, voice frustration and prepare to change course. He couldn’t understand why this one product was taking off and all the others were struggling to gain traction. Accordingly, he would change direction for the underperformers while telling the strong team to carry on.

This story has some rich lessons in leadership that can help others avoid common pitfalls that often afflict product organizations. Let’s explore this more.

Autonomy and trust power the “strong team” forward

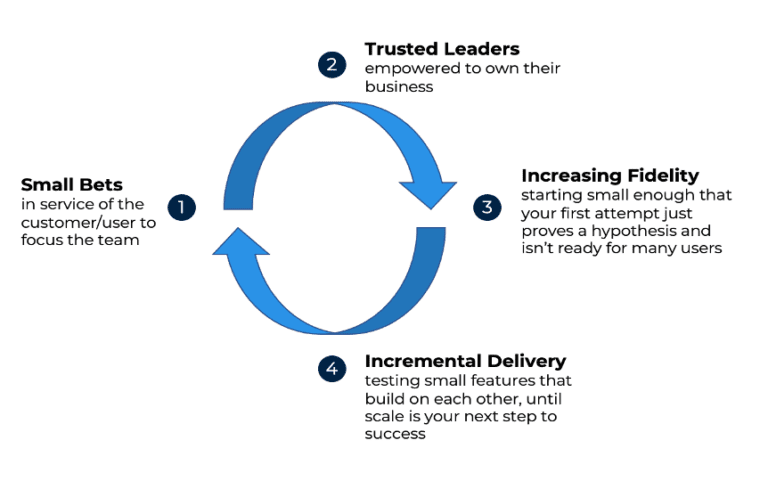

The “strong team” commenced with a focused problem statement, creating a low-fidelity, minimum viable product (MVP) in Excel with a few users. With this small, grassroots effort, the team tweaked the tool to get to a consistent output that satisfied the needs of a small user group. This product started as a side project from an ambitious and creative individual who identified a problem and a clear way to solve it.

Once the MVP was created, the executive placed full trust into this individual, giving him leadership to scale it out to more users. He saw the value, and frankly, this product evangelist was skilled at gaining buy-in. He could assuage the executive’s concerns while protecting the autonomy of his team. He was given the necessary time and space to refine the concept while his MVP was still in use, gaining valuable feedback along the way.

The team decided to productionize the Excel sheet prototype into a SaaS tool. Their only objective was to move their powerful algorithm into an online tool that performed well and could scale to more users. This effort was small, focused, and led by a product team leader who was fully empowered to ensure his group could get it done.

The product had a steady stream of users clamoring to try it. The team continued to focus on how to improve the tool for its power users while also exploring ways to assuage the concerns of detractors and less engaged constituents.

The struggles of fledging teams

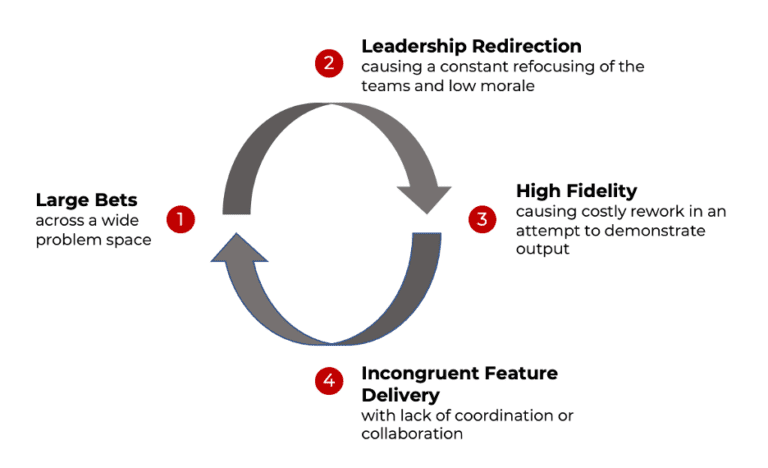

As one team saw rapid success, other product teams in the group were given complex problem statements in other areas of the business. When these teams attempted to focus on one key topic, company executives regularly challenged the team leads as to why that was the problem they focused on. They were often encouraged to think bigger.

When the teams fractured into various workstreams under different product managers, each focused on separate but related problems. They began to run into one another – sometimes delivering features to address overlapping or redundant user problems.

Teams were often redirected away from an effort at hand because it belonged in “someone else’s product space.” However, functionality had already been built into their foundational SaaS platform. Components would now have to be stripped out, which was costly rework the organization would have to bear.

Learn to let go and allow leaders to “lead”

It is easy to see the difference between these scenarios when juxtaposed (a team finding success versus fledging ones). The solution was less obvious in the moment to a stressed executive who was new to digital product management, but vastly experienced in a more command-and-control type of culture.

As an executive in a product-driven organization, one’s role changes. This is often highly uncomfortable to executives who have long called the shots.

What worked so well in the first scenario? The executive had proof that the product would work and trusted the leader in place to take it to the next level. In product, it is up to the executive to communicate a vision and a budget, and then step away to let their team leaders determine how to best make that vision a reality.

This is not to say an executive loses all control, but instead becomes an observer of how their strategy is being carried out. Cultural hangovers, like weekly reviews or the tendency to drift back to a command-and-control style of management when something is creating anxiety can completely disrupt the transition of an organization to a product mindset.

Trust and empowerment are the cornerstones of a high-performance culture

In a product-driven organization, an executive assumes the role of the investor or advisor – one who trusts his or her leaders and teams to be experts in their areas. Product executives provide execution backing and support, some directional coaching through context and expertise, and then decide if they’ve hired the right mix to achieve their goals.

A product-driven culture is about dispersed authority and empowerment. Fewer decisions get “run up the chain of command.” While this may cause headache and heartache for executives who are out of their comfort zone, believing in it for the greater payout is essential.

Product driven organizations are like diversified investment portfolios: they make a bunch of small bets on many individuals to drive the business forward. In doing so, they are diversifying their risk. Gains may be smaller or slower, but they should also be more consistent. Many companies have found great success in this model because it encourages everyone, especially product team leaders, to rise to the occasion, acting as a business owner of their own portfolio.

Unlocking success is within grasp

Only when leadership truly takes on a trust and empowerment approach can product teams unlock their full potential to deliver meaningful and measurable results. In my experience counseling several product organizations in evolving their operating models, this overarching mindset change is often what separates the winners from the aspirants in this highly competitive space.

Want to examine how your organization can implement a product mindset? Please reach out and let’s talk about the practical side of building a high-performance culture in a product organization.